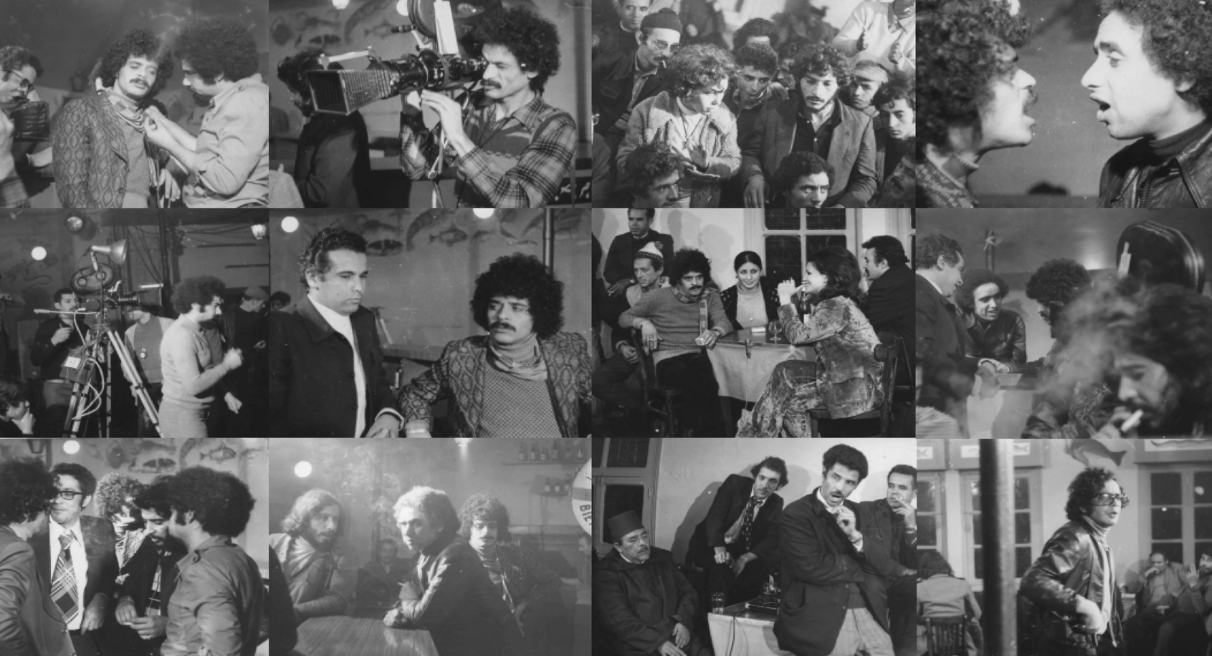

Interview: Mediating Social Media: Akram Zaatari in Conversation with Anthony Downey, Third Text, January, 2019

Akram Zaatari, still from The Script, 2018, single channel video with sound, © Akram Zaatari

Anthony Downey Akram, firstly, congratulations on The Script. I found the film enchanting, and it is, I think, deceptively simple. It’s in two parts: one is set in the Zaatari residence in Saida, and the other in a theatre in Saida. Saida is about forty-five kilometres south of Beirut, and it’s where you were born, of course. I was wondering if you could talk about the genesis of the film, because it was in fruition, or genesis, for about two years, if I understand correctly. And it’s not just about film. It is a film, but its obvious reference points may not be overtly obvious to first-time viewers. Could you talk a little bit about how the film came into being, and your interest in its specific area?

Akram Zaatari The film is entitled The Script because this is a script that has been developed by people, You Tubers, who film themselves and upload their rushes on YouTube. So this is not a choreography or a script that I wrote, but I was inspired by it taking place and unfolding on YouTube and being twisted and changed by different people. You see a man trying to pray, although he is not just trying to pray as no matter how the kids try to interrupt, he continues with his prayer. What I like about it is that there is obviously a choreography written for this, and there has been a rehearsal. So I asked myself, why would people do that? I still don’t have an answer, but it’s amusing and it shows an interesting relationship between father and son, or between grown-up and child. It also shows an interesting relationship between a religious person and an individual (the kid) before they know religion – because at two or four years old, you don’t know what religion is. So for the child, this ritual is more like play, or choreography, and he doesn’t understand why during this particular ritual the father doesn’t interact. If the child tries to catch the father’s attention, the father does not react…

To read full interview, see HERE.

Click HERE to see and download a PDF of the catalogue for the exhibition.

Touring dates for The Script are:

Nottingham Art Exchange, Nottingham, UK

13 July 2018–9 September 2018

http://www.nae.org.uk/exhibition/akram-zaatari—the-script/140

Turner Contemporary, Margate, UK

18 October 2018–6 January 2019

https://www.turnercontemporary.org/exhibitions/akram-zaatari

Modern Art Oxford, Oxford, UK

23 March 2019–12 May 2019

https://www.modernartoxford.org.uk/event/the-script/