2023/31/05 Essay: Mnemotechnics: Digital Epistemologies and the Techno-Politics of Archiving a Revolution

To read the full essay, see here

“The internet has effected an unprecedented historical instance of accelerated image production that has fundamentally realigned the way we view, understand, and disseminate moving images. This may appear to be a truism of sorts but it is currently estimated that over 400 hours of video is uploaded to YouTube every minute. Although it is the second most popular website in the world, this still needs to be put into perspective: if we extrapolate, this means that 24,000 hours of video is uploaded to YouTube every hour which is the equivalent of over half a million hours of footage being uploaded every day. Although it is the second most popular website in the world, this still needs to be put into perspective: if we extrapolate, this means that 24,000 hours of video is uploaded to YouTube every hour which is the equivalent of over half a million hours of footage being uploaded every day.”

To ready the full essay, please click here.

“Transposing the Vernacular: Moving Images in the Work of Akram Zaatari”, is catalogue essay published on the occasion of Akram Zaatari’s touring show, The Script, launched at the New Art Exchange (13 July — 9 September 2018). It toured to Turner Contemporary (19 October 2018 — 6 January 2019), and Modern Art Oxford (23 March — 2 May 2019).

“On 2 March 2012, the precincts of the City Civil Court in Bangalore, erupted into mayhem as a pitched battle broke out between members of the judiciary and local media groups. These skirmishes quickly degenerated into acts of vandalism and the local police force waded in with a lathi-charge — or baton charge — to restore order. Three months before these events, the same judicial advocates had staged a boycott of the courts, following an unprovoked attack on one of their members by police. This attack was part of a pattern of intimidation and harassment that, as far as the judiciary were concerned, was impeding their ability to carry out their duties. Infuriated by police harassment and, at the time, the adverse media coverage of their strike (which they considered both legitimate and necessary), the judiciary turned their anger towards the media”.

To read full essay, please click here

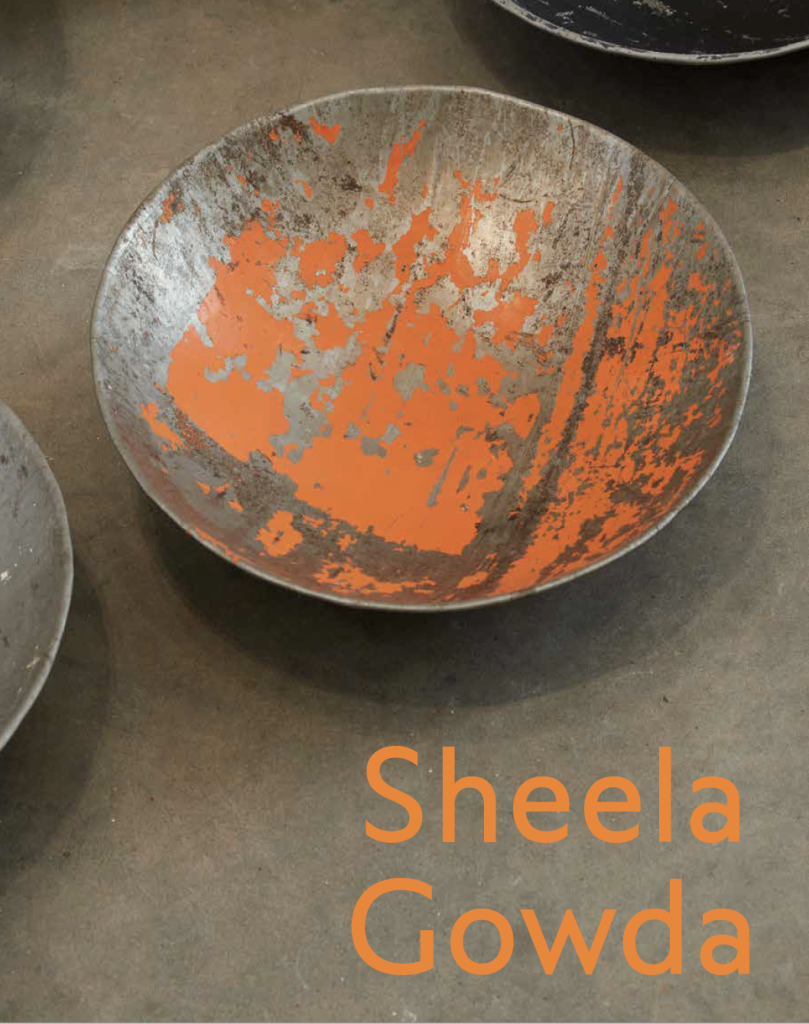

“Where to Now: Imminent Impermanence in the Work of Sheela Gowda”, is a catalogue essay published on the occasion of Sheela Gowda, Ikon Gallery, November 2017.

An edited version of this essay, also titled “Where to Now: Imminent Impermanence in the Work of Sheela Gowda”, was included in the exhibition catalogue for Sheela Gowda’s retrospective show, Remains, at Fondazione Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, April 4th to September 15th, 2019, with other critical essays by art historian Geeta Kapur and writer and curator Pablo Lafuente, a text on the show by the curators as well as well as contributions by Roger M. Buergel, Grant Watson, Abhishek Hazra, Jessica Morgan, Zehra Jumabhoy, Marta Kuzma and Tobias Ostrander.

In October 2019 an adapted version of this show will travel to Bombas Gens Centre d’Art, Valencia.

May 2017

Don’t Shrink Me to the Size of a Bullet: The Works of Hiwa K

Edited by Anthony Downey.

Contributors: Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Natasha Ginwala, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Aneta Szyłak, and Bakir Ali.

Publisher: Walther König Verlag.

Publication Date: May 31, 2017.

244 pp.

Colour illustrations.

Last time I saw my mom before my farewell, I said, “Mom, I am leaving for good. I don’t know… maybe I will not make it like the other 28 people who got shot last week” . She said “Son, if death comes, don`t panic. It is just death”.

Hiwa K, “Don’t Panic”, 2016

Covering over decade of projects, Don’t Shrink Me to the Size of a Bullet: The Works of Hiwa K provides the first comprehensive account of the artist’s practice to date. Edited by Anthony Downey, with a foreword by Heike Catherina Mertens and Krist Gruijthuijsen, the volume includes essays by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Natasha Ginwala, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Aneta Szyłak, and a conversation between the artist and Bakir Ali. A series of texts have been prepared and revised by the artist, and he has also included a collection of anecdotes that recount gossip, stories, jokes, personal insights, conundrums, and aphorisms garnered from multiple sources. These have all been translated into Kurdish for the first time. The volume is fully illustrated and will contain extended notes on the works.

To read Anthony Downey’s essay, “Unbearable States: Hiwa K and the Performance of Everyday Life”, see here

Don’t Shrink Me to the Size of a Bullet: The Works of Hiwa K was launched at KW (Berlin), 31 May, and Documenta 14 (Kassel), 11 June, 2017.

Buy the book here.

ISBN 978-3-96098-160-2

February 2017

‘I see only from one point, but in my existence am looked at from all sides.’

– Jacques Lacan

“From the opening of Richard Mosse’s film Incoming (2016), it is evident that we are looking at something disturbingly vivid. Abstract images, grounded in a resounding radar-like echo, give way to the supersonic pitch of a strident, purposeful engine. A tenebrous image of a fighter jet strafing a town with laser-like intensity, its nose incandescent with heat as it fires round after round of needle-like missiles, appears almost languid and disconcertingly graceful in its livid ambit. An anti-aircraft gunfires back, no doubt in vain, at this incredibly fast moving object,while explosions are registered as bleached out columns of billowing phosphorescent light. Subsequent images show a ship boarding people from a rubber dinghy, their forms bleached out and spectral. Moments later, we see the irradiated deck of an aircraft carrier complete with fighter jets undergoingpreparation for imminent attack. This could be a video game or hell incarnate – or, potentially, both”.

To read full essay, please click here

To listen to Richard Mosse in conversation with Anthony Downey, Barbican Centre, 2017, please click here.

To purchase a copy of Richard Mosse, click here.

December 2016

There is a momentous process happening across the Middle East and North Africa today. It is an insidious development, partly surreptitious but mostly blatant in its operations. It is an evolving phenomenon that affects numerous people and communities, albeit to different degrees, and yet remains, with a few exceptions, unobserved. This development, if allowed ascendancy, will present an insurmountable obstacle to social, political, economic and cultural progress across the region. It will also hinder and obstruct relations between individuals and within communities for generations to come.

Future Imperfect: Contemporary Art Practices and Cultural Institutions in the Middle East launched on 22 February 2017 at Delfina Foundation, London.

Read the full essay and introduction.

To read the introduction to Volume 01 in this series, Uncommon Grounds: New Media and Critical Practices in the Middle East, see here.

To read the introduction to Volume 02 in this series, Dissonant Archives: Culture and Contested Narratives in the Middle East, see here.

To purchase a copy of Future Imperfect please follow this link.

6 October 2016

Tarek Al-Goussein, from the exhibition The People of the Sea, Haifa.Copyright the artist

Read original publication here

In 2005, the Palestinian author, activist and academic Ghada Karmi returned to Ramallah to work as a consultant for the Palestinian Authority’s ministry of media and communications. In her recently published memoir covering her extended time there, Return (2015), she recounts the travails of that role alongside her all too potent memories of places and towns she had not seen since her childhood. Exiled from Palestine in 1948, and thereafter settling in Britain, Karmi describes herself as a ‘full-time Palestinian’ – an activist dedicated to the one cause that has given her life meaning: redressing the historical dispossession endured by the Palestinian nation. Despite the sense of occasion and expectation engendered by her return, Karmi’s journey was a less than triumphant event. Finding herself bogged down by the internal politics involved in her new role, and by what she views to be counter-productive defeatism in some quarters and narrow opportunism in others, she resorts to a view that the overarching narrative of historical dispossession has been reduced, by the pervasive influence of the Israeli state, to a day-to-day struggle for survival. This struggle, for her, has effectively usurped any unified sense of a national struggle, or indeed any prospect of a resolution to the abject reality of living under occupation. At one particularly low point, Karmi goes as far as to question her own motives as a returnee, so to speak, and states the following: ‘Flotsam and jetsam, that’s what we have become, scattered and divided. There’s no room for us or our memories here. And it won’t ever be reversed.

Karmi’s Return raises countless questions, and does not make for comfortable reading for all concerned. There is no sense of the catharsis associated with insight; nor is there any sense that the traumatic acknowledgment of historical loss holds out a remedial degree of reconciliation. On the contrary, Karmi find herself doubting the very possibility of representing the reality of modern-day Palestine in all its logistical complexity and all too resonant state of exceptionalism. The conundrum of representation – under the historical conditions of occupancy and the looming exigencies of the present – is a significant and far from resolved feature of Karmi’s book: how do you represent a reality that has been not only sundered by historical forces but remains subject to the fluid and all too fractious, if not arbitrary, demands of an occupying force? What is it, moreover, to engage with the legacies of occupancy and dispossession in the present moment through the rhetoric of individual involvement? This question, of course, is central to any consideration of how contemporary culture engages with and attempts to define the realities of modern-day Palestine. In a milieu defined for many by ascendant forms of political exceptionalism (where the reality of the camp, the refugee and the dispossessed have all become the exemplary, rather than exceptional, symbols of late modernity), how do you, furthermore, represent a state of being that is often denied legal, political and historical representation?

These questions remain central to any over-arching consideration of how contemporary visual culture engages with and represents the exceptional state of being that is day-to-day life in Palestine. There are no easy answers here and, given the fact that Palestine is both a heavily militarized zone and yet remains for many a relatively indistinct one (positioned as it is outside of international law and the sovereign forms of self-governance associated with a state), the politics of representation needs to be consistently articulated here within a series of self-reflexive questions. How do you represent, for example, that which remains suspended within legal and political forms of representation? How do you avoid over-aestheticizing the reality of living within, say, the West Bank or Gaza, so that it becomes symbolic of suffering in general? If Palestine, moreover, is indeed indicative of a prevalent form of strategic spatialization and the quartering of social, political, ethnic and economic relations, then to what extent do strategies of representation need to fully explicate the specificity of this condition and conditioning rather than merely reify it as a form of spectacle?

Sophie Shannir, from the exhibition The People of the Sea, Haifa. Copyright the artist.

These are, amongst others, the challenges faced by artists in relation to Palestine today and we could further observe here the need to consider the means of production and the form the work takes (what does context do to an image); the context of spectatorship (who is looking and why); the institutional infrastructures involved in the dissemination of images associated with Palestine (who benefits from these images); the means of display (where is it shown and how); and the role of the artist as a quasi-ethnographer-cum-witness in an economy of images that looks at the politics of ‘return’ and the modalities of being that underwrite (and sometimes undermine) the diasporic condition. All of these elements need to be taken into account if representation is to offer a productive and interrogative means for representing such an exceptional reality.

We turn here to a broader concern and a vital element in any consideration of cultural production today: the vectors of association to be had between recent conflict and upheaval within the region and the demands placed upon artists and cultural institutions to ‘report’ these events for global consumption. This is an essential consideration when it comes to understanding why a significant number of international institutions now profess to ‘represent’ conflict, and how the artistic, critical and curatorial legitimacy conferred on these works is often part of a broader continuum of global commodification. Moreover, the ‘value’ associated with images of conflict and dispossession is rarely accrued by the subjects depicted therein, which leads us to the all too pertinent question of agency: who gains from a work of art that purports to represent conflict? Is it the subject of conflict – the migrant, the refugee, the dispossessed, the disappeared – or the artist, gallery, sponsor, non-governmental agency, investor or institution producing and showing the work? This concern may be more institutionally problematic than it initially sounds if we enquire further into the nature of how institutions benefit not only in terms of capital when they invest in artworks, but also politically and socially from their association with images of conflict. The question, simply put, is straightforward enough: who benefits, institutionally, financially, socially, politically and historically, from the work of art when it purports to engage with the realities of Palestine today?

Nida Sinnokrot, Flight – Jalazone, 2016. Part of the exhibition Sites of Return, Ramallah. Copyright the artist

Needless to say, these issues are all the more attenuated when we consider the broader representational conundrums associated with Palestine and the extended region of the Middle East. We could note, for one, how the region is currently undergoing a significant degree of political upheaval and social turmoil. Revolution, uprisings, internecine warfare, civil conflict, and human rights, all of these points of reference have been deployed in an intensification of interest in the region and the coextensive demand that culture either condemns or defends such events and notions. Again, this is an international rather than provincial concern, inasmuch as there remains the ever-present interpretive danger that visual culture from the region is legitimized through the media-friendly symbolism of conflict – the latter rubric being redolent of colonial ambitions to prescribe the culture of the Middle East to a set of problems that revolve around atavistic conflict and extremist ideology. Such concerns, voiced in the wake of uprisings across the region, remind us that colonial paradigms are not only far from defunct, but easily resuscitated through an evolving neo-colonial preoccupation with topics such as an (apparently) irresolvable form of atavistic conflict brought about by an equally irredeemable strain of dogmatic extremism.

Apart from the imminent need to consider the historical contexts out of which this current state of affairs has emerged, and how cultural production has engaged with these frames of reference, the unrelenting instrumentalization of cultural production so that it answers to a global cultural economy must be likewise investigated. Increasingly, and nowhere more so than in an age of deregulation and the dominance of the global culture industry, contemporary art institutions have become more and more involved in forms of promotion, marketing, merchandising, entrepreneurship, sponsorship, community-based programmes, educational courses, expansionism, and the development of transnational networks. This would seem to be a structural necessity in a period defined by hyper-capitalism and the demands of a neoliberal, global economy. Globalization, in this context, and in conjunction with the neoliberal policies that enable its dominance, not only produces rampant forms of ‘uneven development’ but also co-opts cultural economies into the realm of a privatized, overtly politicized ethic of production, exchange, and consumption.

Santiago Rizo Zambrano, Democratisation of the Land. Copyright and courtesy the artist.

Given these conundrums and ambiguities and, frankly, the far from resolved issues around representation, it is all the more gratifying to see the 3rd iteration of Qalandiya International (Qi) in place and how it confronts, rather than avoids or abnegates, precisely the terms of these debates as points of departure. This is a brave undertaking and it is, if I may say, an honour for Ibraaz to act as the international media partner for such an important and self-reflexive event that refuses to shy away from, nor disavow, the complexity of representational strategies when it comes to the reality of Palestine and the broader Middle East. It is, moreover, precisely the role that Ibraaz was set up to perform by our parent organization, the Kamel Lazaar Foundation, in 2011 when we endeavoured to initiate a platform that would be solely dedicated to producing critical knowledge, free for all who visited our website, about the politics of knowledge production and the challenges faced by cultural institutions across the region. We are, and remain, fully aware of the logistical problems associated with bringing institutions, cities and people to together in Palestine and it is a substantial achievement to not only bring together 16 art and cultural organizations from within and beyond Palestine but to have them communicate with one another. I hope, on an albeit modest level, that Ibraaz‘s publication of the online catalogue for Qalandiya International will reveal some of that ambition and communicate it, across our digital platform, to an international audience and cohort of supporters.

There is a sense, as noted by the organizers in their introductory text, that we must acknowledge the extent to which the so-called ‘return’ project has been diminished to the symbolic realm of visual culture and, thereafter, reassert the degree to which art as a practice is always a social act – a practice that is indelibly imbricated within and often evolving alongside social and political concerns. This is not only evident in the curatorial remits presented here in this online catalogue, but also in the sense that culture has a part to play in defining the terms of the debate about political self-determination and history rather than occupying, so to speak, a position outside or alongside them. This is not, finally, about art practice as a form of political protest (an all too easily co-opted cultural paradigm), nor is this to confuse the artist as protestor (or vice versa). Rather, as we can see throughout the 2016 iteration of Qalandiya International, this is about the potential of art to open up horizons of possible engagement with the politics of return and the complexities associated with the diasporic condition. It is to the credit of Qi that, rather than elide or fetishize such concerns, it embraces the very problems in hand and offers creative forms of exchange and contact to more fully understand and engage with issues that can often appear intransigent, if not interminable.

30 May 2015

How do we define the ongoing relationship between contemporary art and the archive? Considering the unprecedented levels of present-day information storage and forms of data circulation, alongside the diversity of contemporary art practices, this question may seem hopelessly open-ended. In an age defined by the application of archival knowledge as an apparatus of social, political, cultural, historical, state and sovereign power, it nevertheless needs to be posed. In what follows, I will suggest that we can more fully refine the question and offer a series of conditional answers if we consider, in the first instance, the extent to which contemporary artists retrieve, explore and critique orders of archival knowledge.

Read the full Introductory essay.

Contributors:

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, John Akomfrah , Jananne Al-Ani, Meriç Algün Ringborg, Héla Ammar, Burak Arıkan, Ariella Azoulay , Vahap Avşar, Sussan Babaie , Alessandro Balteo Yazbeck, Timothy P.A Cooper, Joshua Craze, Laura Cugusi, Ania Dabrowska, Nick Denes, Chad Elias, Media Farzin, Mariam Ghani, Gulf Labor, Tom Holert, Adelita Husni-Bey, Maryam Jafri, Guy Mannes-Abbott, Amina Menia, Shaheen Merali, Naeem Mohaiemen, Mariam Motamedi Fraser, Pad.ma, Lucie Ryzova, Lucien Samaha, Rona Sela and Laila Shereen Sakr (VJ Um Amel).

Dissonant Archives: Contemporary Visual Culture and Contested Narratives in the Middle East launched on 30 May 2015 at JAOU Tunis 2015 at the National Museum of Bardo, Tunis.

To purchase a copy of Dissonant Archives please follow this link.

15 November 2013

Film still from Episode 1, Renzo Martens (2003), installation at FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), Liverpool as part of My War (2010). Images courtesy of FACT.

Today, we are in an intervallic period in which the great majority of people do not have a name. The only name available is ‘excluded’, which is the name of those who have no name.[1]

Alain Badiou, ‘The Caesura of Nihilism’

And so I must carry with me, through the course

Of pale imaginings that leave no trace,

This broken, idle mill-wheel, and the force

Of circumstance that still protects the place.[2]

J H Prynne, ‘Force of Circumstance’

Lives lived on the margins of social, political, cultural, economic and geographical borders are lives half lived. Denied access to legal, economic and political redress, these lives exist in a limbo-like state that is largely preoccupied with acquiring and sustaining the bare essentials of life. The refugee, the political prisoner, the disappeared, the ‘ghost detainee’, the victim of torture, the dispossessed, the silenced, all have been excluded, to different degrees, from the fraternity of the social sphere, appeal to the safety net of the nation state, and recourse to international law. They have been out-lawed, so to speak: placed beyond recourse to law and yet still occupying a more often than-not precarious relationship to the law. Although there is a significant degree of familiarity to be found in these sentiments, there is an increasingly notable move both in the political sciences and in cultural studies to view such subject positions not as the exception to modernity but its exemplification. Which brings us to a far more radical proposal: what if the fact of discrimination, in all its injustice and strategic forms of exclusion, is the point at which we fi nd not so much an imperfect modern subject — a subject existing in a ‘sub-modern’ phase that has yet to realize its full potential — as we do the sine qua non of modernity; its prerequisite as opposed to anomalous subject? What if the refugee, the political prisoner, the disappeared, the victim of torture, the ‘ghost detainee’, and the dispossessed are not only constitutive of modernity but its emblematic if not exemplary subjects? (more…)