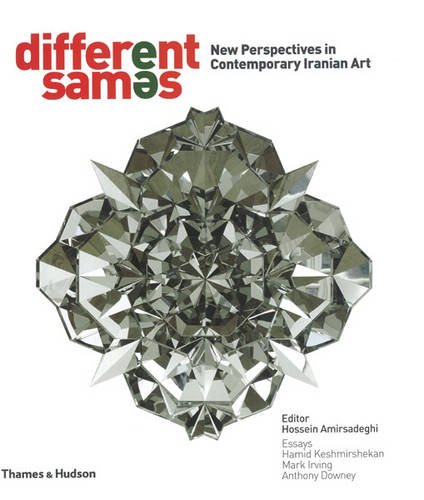

Different Sames: New Perspectives in Contemporary Iranian Art

Thames and Hudson, 2009 | CO-AUTHOR

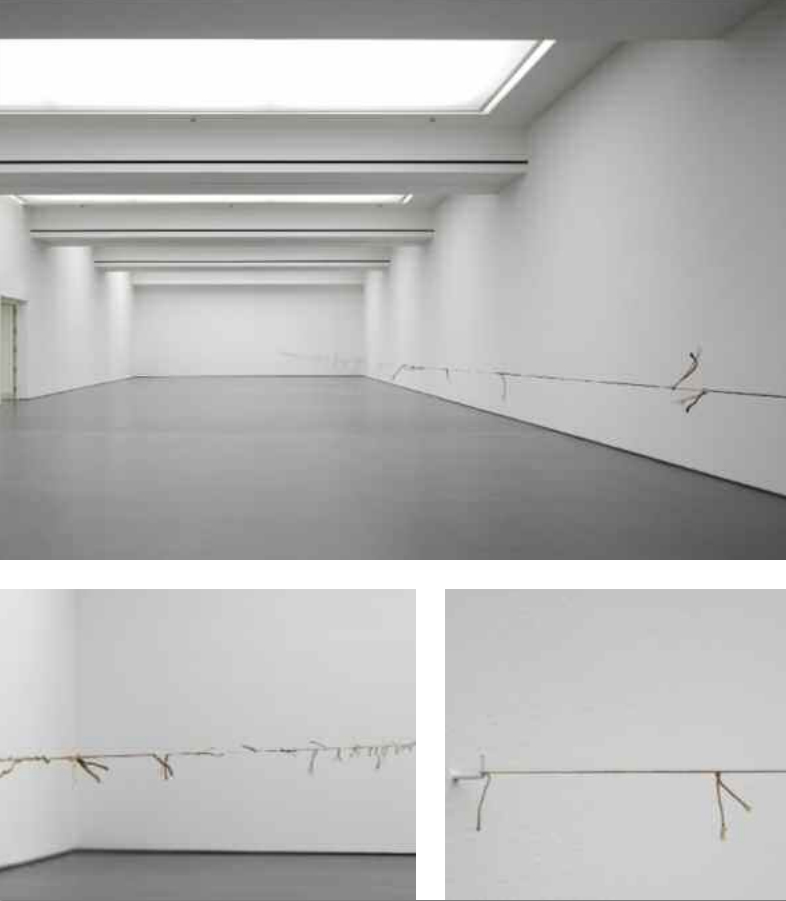

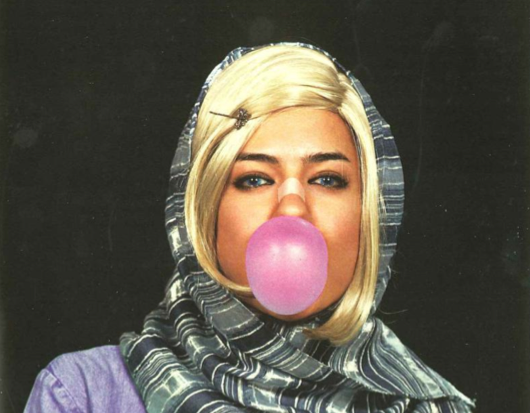

Long considered a bastion of creativity in the region, Iran is currently experiencing a remarkable artistic revival in the middle of the most challenging of circumstances. Different Sames catalogues this new movement, capturing its brilliance and creative energy. Packed with wonderful images, it is an important and lively compendium of thought provoking essays, historical context and profiles of the country’s leading contemporary artists. Art changes the way we look at the world, and Different Sames is an attempt to explain todays Iranian art movement in this spirit.

Long considered a bastion of creativity in the region, Iran is currently experiencing a remarkable artistic revival in the middle of the most challenging of circumstances. Different Sames catalogues this new movement, capturing its brilliance and creative energy. Packed with wonderful images, it is an important and lively compendium of thought provoking essays, historical context and profiles of the country’s leading contemporary artists. Art changes the way we look at the world, and Different Sames is an attempt to explain todays Iranian art movement in this spirit.

Chapter authored: Diasporic Communities and Global Networks: The Contemporaneity of Iranian Art Today.

To purchase a copy of Different Sames: New Perspectives in Contemporary Iranian Art please follow this link.

Reference

Keshmirshekan, Hamid, Mark Irving, and Anthony Downey. Different Sames: New Perspectives in Contemporary Iranian Art. Ed. Hossein Amirsadeghi. London: Thames & Hudson, 2009.