From Invisible Enemy to Enemy Kitchen: Michael Rakowitz in conversation with Anthony Downey

29 March 2013

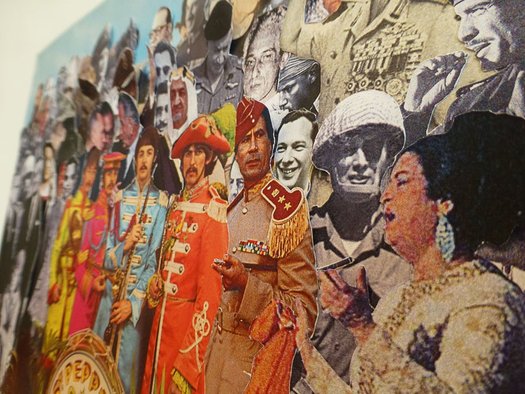

Michael Rakowitz, Detail of The Breakup, 2012. Original Sgt.Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover (1967) magazine color printouts 12 x 12 inches, 30.5 x 30.5 cm. Courtesy the artist and Lombard Freid Gallery

Michael Rakowitz is an Iraqi-American conceptual artist whose work is influenced by his cultural origins, not so much in terms of identity, but as a means through which to engage issues that affect cultural production and the loss of culture. An artist with a concern for the economies of exchange that inform social, political and historical events, it is in the contested realm of human experience that Rakowitz situates his practice. However, rather than offering solutions to forms of social inequality and historical injustice, or attempting to ameliorate social and cultural loss, Rakowitz’s practice is more about agitation and the antagonistic counter-narratives that continue to re-emerge in any accepted version of events.

In this interview with Anthony Downey, he discusses projects such as The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (2007) and his ongoing project Enemy Kitchen that started in 2004. He also talks about his 2012 project, presented at dOCUMENTA (13), and its focus on the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, the latter having been destroyed in 2001 by members of the Taliban, and The Break Up, 2012, which examines the apparently unlikely relationship between The Beatles, the Six Day war in 1967, and the dream of Pan-Arabism.

Anthony Downey: I want to talk to about The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (2007), in which you recreate objects looted from Iraq’s National Museum. It brings into play not only archeological issues, but issues of tourism and repatriation – something I find throughout your work – not to mention issues around cultural looting. Can you talk about how this work came into being and if this term ‘recuperation’ means anything to you in this context?

MR: The work deals with addressing a void and finding ways of articulating in some visual and spatial sense what everybody says is lost. In 2003, we became a global viewing public with the information that the cultural heritage in Iraq had been wiped off the face of the earth because of the allied invasion. With that in mind, it was almost like the abstract details of it were enough to create what I felt was the first moment of pathos in the war. Whether you were pro-war or against the war, right or left, Iraqi or American, or just somewhere else on the globe, this was not an Iraqi problem, this was a human problem. It was almost a missed opportunity for people not just to be outraged by objects going missing but by actual bodies going missing. It’s like what happens when you get a photograph of a mass grave; you’re never able to focus on the individual things or people, it’s always just a big abstraction. What was recuperative was this restoring a sense of what each of these things once were. And that is why I set about recreating some of the objects that had went missing. In the process of attempting to remake something that clearly can’t be remade there is also this kind of additive effort that comes through when making these things.

I’m also interested in this idea that you can never reconstruct history – we all know that these things are gone forever and these are just surrogates made with the immediacy of detritus being enlisted as a material. It’s almost like a futile effort. But I think it was also recuperative. This was the first project I did after moving to Chicago from New York, working with these young artists who are from the American heartland between 2006 and 2007. There was this war that none of us could do anything about, which we couldn’t stop, and there was something about the slowness about making this work that allowed for a conversational space to open up where we were actually discussing the war. That moment in 2007 actually feels far enough away now for me to be really able to actually log it as a time when the American psyche was feeling these complicated emotions about complicity and a certain kind of impotence at what could be done, if anything. In making these things, we didn’t replace the original things, but there was something recuperative and hopeful about it while, in time, admitting its failure in terms of whether it adequately replaces something that was lost.

AD: It’s interesting you use the word ‘pathos’, which comes from the Greek ‘pathetic’ and is used to define an appeal to emotions that is ultimately doomed to failure. With The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, it seems the finished product, whilst important, is not as important as this appeal to an audience to engage; but also to the process in making that work with collaborators. Do you think the process is more important here?

MR: You can look at it in different ways, but I’m going to be biased because I’m the maker and I went through the experience of making it in my studio – nobody else experiences that. I don’t think it’s necessarily the critical moment of the work and I wouldn’t, for instance, show a video of the work being made, because I don’t think it is always necessary to elaborate on those backstage moments. I’m also very considered in terms of what to put out there for the end piece and I think the objects do speak about their making in a way, because – like you said – there is a certain kind of pathetic quality in terms of what materials are being used. It’s the waste: the foodstuffs, packaging, newspapers, detritus, and the discarded moments of culture. I don’t think it’s necessary to over burden the work with information about how it’s made.

AD: Many of your other works play with institutional contexts. They are very much, in this instance, mimicking artefacts within the museological context. They are also invariably not site specific as such but more context-based and in dialogue with the institutions within which it is placed. Does that have purchase on the way you think about the development of these works? I’m thinking about What Dust Will Rise, which was shown at dOCUMENTA(13) in 2012.

MR: I’m an artist who started out as a public artist and worked site-specifically. This idea of matching up contexts and working institutionally is another way of being site-specific. It is very much on my mind, but I should talk a little more about The Invisible Enemy and how it largely came out of a similar acknowledgement. The Invisible Enemystarted out as a gallery piece and the museological aspect really bloomed when it went to places like Sharjah or the British Museum or Modern Art Oxford; the site specificity meets there. But walking through Chelsea in 2006, it occurred to me that you wouldn’t know that we were living in a war culture in New York City. There was really no work that dealt with the fact that there was a war going on – it seemed to be business as usual. I wanted to address that and jolt people’s complacency. For years, I’d been thinking about re-making the aretefacts that were lost. But then the more I read about the museum looting, the more complicated it became to cry about missing artefacts: for Iraqis, looting the museum and selling an artefact on the black market was a way to get out of the country. The existence of the antiquities market allowed for the museum to be looted in the first place, and here I am pressured to do another show at the gallery and dealing with the market.

Since the project was born out of selling something from a commercial gallery, being shown for the first time in an institutional setting in Sharjah was the moment it shifted for me. I wasn’t sure how a public in the Middle East, as opposed to the United States, would perceive it in a museum only 800 miles from Baghdad with a lot of those artefacts having been trafficked through the United Arab Emirates before ending up in private collections around the world. The British Museum is a really interesting one for me because they bought a grouping of the artefacts created from the project as a way to critique their own history and I’m looking forward to when they put those on display. They are supposed to put the looted artefacts from their own collection on display with the ones I’ve made. I’m interested in what kind of tension will be achieved between these two things.

For dOCUMENTA(13), I went in with a twofold project. One was to address the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan because Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev was doing a whole position of Documenta in Afghanistan. This has interested me even longer than the Iraq Museum because I was trained as a stone carver from when I was fifteen and my teacher actually showed me the Bamiyan Buddhas at that moment in my life. What I did was more or less a tribute to them. But in this case of absence, something different goes on in the Bamiyan Buddhas because when talking to people on the street in Bamiyan, they will tell you that they are still there. In fact, they are even more defined because their absence has re-inscribed their presence more than when they were standing there. It’s really incredible to hear people speaking that way and I thought, instead of rebuilding the Bamiyan Buddhas I’d rather re-introduce or re-distribute the skillsets that allowed for them to be made in the first place. That was how the idea of a stone carving and calligraphy workshop came about. For one week, I worked in collaboration with a German sculptor and restorer who has worked on the Bamiyan site since 2004, Bert Praxenthaler. We did this workshop at a cave right near where one of the Buddhas had stood. Students from the area who were not art students – there were six women and six men – and we carved stone. For me that was a piece in itself because you had this redistribution of that skillset happening in the same frame as the absence that marks the destroyed artifact of the Bamiyan Buddhas.

One other part of the project was looking at the Fridricianum in Kassel as a site where this work would be shown. I found myself in the archives and looking at the building after the British had bombed it in 1941 and seeing all these destroyed books. One of the books was the theory of rhetoric by Cicero, which had been previously damaged much earlier because Benedictine monks had scraped away a lot of the text because it was un-Christian. You have all these different levels of iconoclasms that happen either through state rhetoric or religious dogma. I thought about reconstructing those books; burned in these ways that made them look like they became petrified or scared. The idea of carving them in the stone of Bamiyan became a moment of intersecting those two moments: one moment of cultural destruction with another.

AD: There is this book by Raymond Williams Baker, Cultural Cleansing in Iraq: While Museums were Looted, Libraries Burned and Academics Murdered. Baker argues that the lootings of the museums in Iraq was not only permitted and enabled by the Allied forces because they believed that if you could eradicate culture it would be easier to build a new state, it was actively encouraged. I’m not necessarily saying it chimes with your work but I think it is an interesting way of looking at that looting, not even as something to do with artefacts being circulated on a global level, but the literal evisceration or deracination of Iraqi culture that seemed to be a policy – as opposed to a byproduct – of the invasion of Iraq. It is one moment of eradication, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, being met with another: the looting of museums.

MR: That makes a lot of sense. In What Dust will Rise there is this one quote placed in one of the vitrines that houses the relics of the Western Buddha of Bamiyan and it’s from Mullah Mohammed Omar, who more or less alludes to the fact that the reason he blew up the Bamiyan Buddhas was not because he wanted to destroy them. In fact – and this is true – it was because he met with the Taliban elders who said that they shouldn’t be destroying this because its part of Afghanistan history and it’s an essential tourist site. Then apparently, these Swedish archeologists or professionals wanted to give money to have the Bamiyan Buddhas restored for damage. When he asked if they could use that money for food for suffering Afghani women and children they said no because it was for the Bamiyan Buddhas. He thought this was deplorable and decided to blow them up as a result. If they had come for humanitarian work he would never have destroyed them but he thought it was one of these things that needed to happen. Not just as a punishment to the west or some sort of admonishment, but also as a way of getting rid of distractions and redressing what he viewed to be inequities in western approaches to Afghanistan.

AD: I note that a number of commentators often talk about so-called ‘relational aesthetics’ when discussing your work but I see this is as a bit of misnomer. I view your work as being more about aesthetics of relating to specific socio-cultural moments in time, be they submerged or overt in their symbolism. With Return (2004) there is a different type of recuperative gesture happening. It is very much about a familial connection: recuperating a relationship that is important to you but, in that moment of recuperating, it is a work that also points to a series of geo-political relations.

MR: Yes. And I’m not going to get started on relational aesthetics. What artwork isn’t relational? There is a certain kind of fluffiness that has risen in this dialogue around work that is based around social practice, which is even worse since it’s been reduced down to an abbreviation where people call it ‘SO-PRA’: this feel-good, almost misplaced kind of ministerial work. What I’m doing in Return is to essentially re-open my grandfather’s company because I realised how absolutely impossible it was to move things around, whether it would be sending things to or out of Iraq. The date syrup was something I became interested in because it is an incredibly symbolic food in Iraq and I grew up around it. Then there was also the family photo album; we had such an incomplete archive of the family’s history in Baghdad because they had to leave under duress. In a lot of ways the project does do these things where it reconnects those relationships; the reason my grandfather came to be an importer and exporter when he was exiled from Iraq was because he was heartbroken at not being able to be Iraqi anymore so he opened the company to stay in contact with his Iraqi partners. That to me was something that echoes in the work where I’m sort of re-entering the market place as this American businessman, because I did open the company legitimately and rebuilt these connections.

AD: There is a quote where you write, ‘I wanted to sit in a place where dialogue would be available’, but of course the dialogue itself in Return didn’t seem to be centred on the shop itself, but the external extraneous, global, virtual participation of individuals. This work comes out of an earlier piece, Enemy Kitchen (2004-ongoing), which was a much more overt engagement with the politics or the legacy coming out of the war in Iraq. I feel that work, despite its apparent simplicity, is extraordinarily complex. It offers a platform for people to speak about the politics of war through the aesthetics of cooking.

MR: For me the idea of bringing these things home in a sense is a kind of remote nature of the war, which was something that I was really struck by since the first Gulf war began in 1991. That was when I was really coming into some sense of understanding of where I come from. I was in my senior year in high school and the place my grandparents had fled to was going to bomb the place they’d fled from and I had grown up with these magical stories about Baghdad. My grandmother used to tell me these stories about singing towers that told the time – minarets - that inspired an earlier piece of mine calledMinaret (2001- ongoing). Then the first time I actually see Baghdad is through the green tinted images of CNN and unidentifiable pieces of architecture being blown up. That to me was really traumatizing from a distance because I felt split: I was half American, half Iraqi, raised completely in the United States.

My mother would always talk about the way Iraqis had been reduced to being these villains and more or less trivialized. It was a culture that she herself felt connected to, even though her family had been expelled it was still a place where urban planning began, which is one of the reasons why I have such an interest in architecture. She would always make Iraq present at home in some ways through her cooking, but I grew up thinking it was Jewish food because it was what we had at Shabbat or Rosh Hashanah: I didn’t even know what matzo balls were until I was in college! All of a sudden, I understood the difference and the sameness that is basically Iraqi food; it was Christian, Muslim, Arab and Jewish. It was all these things that were indiscernible from one another.

AD: You’ve mentioned this notion of the ‘aesthetic of good intentions’. I think the actual phrase is only understandable in the context of your former tutor, Krzysztof Wodiczko. His ideal of ‘interrogative design’ chimes interestingly with the ‘aesthetic of good intentions’. I think with Wodiczko’s work it’s this kind of critical design practice, this manner in which it brings to light a marginalization, or marginal social communities – giving legitimacy to cultural issues so that they can be discussed. Are the ‘aesthetics of good intentions’ and ‘interrogative design’ central to your earlier work, such as paraSITE (1997), for example?

MR: paraSITE came out of a visit to Jordan and it was a very important trip for me: the first time anyone from my family had been back to the Middle East. It was 1997 so I must have been 23-years-old and I ended up wanting to study the architecture I’d seen in Palestinian refugee camps. I’d seen a photograph of a family whose home had been bulldozed by Israel and in a kind of oppositional act they rebuilt the entire façade of the house using discarded aluminum and things like that. I wanted to visit these tents but I was on a residency with MIT and Oxford Brookes and the Jordanian government wouldn’t allow it. I ended up researching the tents and the equipment of the Bedouin, those who were nomadic through conflict and those who were nomadic by tradition. It it came out of looking at the way the tents of the Bedouin were constructed in acknowledgement of the wind patterns that move through the desert and the I saw the wind being blown out of buildings from the external exhaust ports of the heating systems, which gave rise to the thinking behindparaSITE as an actual object. It was also meant to be antagonistic: in French ‘para’ means to ‘guard against’ so ‘para-site’ is to guard against becoming a site; against permanence and to look at the celebration of a certain kind of nomadism. One of the misunderstandings of that project is that it is about benevolence, but it is about creating a moment of comfort that creates discomfort on the street and in those who look at it and the conditions it speaks to and about.

To return to your question regarding ‘good intentions’: a lot of social practice projects have good intentions, and I’ll be the first to understand the critical and negative reception that a lot of that work has had, yet I feel like I need to align myself with those works because I understand the impulse that generates them. I’d been thinking about wrestling with the uneasiness I have with both the work and the critique of the work. But I also have misgivings and scepticisms about putting forward the community alibi. The idea that this was good for the community or the community enjoyed this or was successful because there were all these people that came over for dinner, to me that is not a very convincing artwork. But maybe the aesthetics of good intentions could be that there is something that could rise out of it or maybe it is just bullshit. I’m also interested in the possibility that all of this may play out to reveal something that could be considered an aesthetic or on the way to being something like that. In this sense, perhaps Wodiczko’s ideal of ‘interrogative design’ is closer to what I wanted to achieve there.

AD: I want to return to where we began and look again at this notion of historical recuperation, I was fascinated by but sorry to have missed your show at Lombard-Freid Projects, New York The Break Up (6th September – 17th October 2012). One of the things that fascinated me about this work concerns what was lost in 1967 following the Six-Day war – the dream of pan-Arabism – that you relate to the break up of The Beatles. Could you talk a little bit about that?

MR: I didn’t want to produce a polemic on Palestine. I wanted to figure out if there was a way of doing something that could be related directly to the citizens of the city and places beyond the city, something that people could have access to. I thought about radio: something that travels invisibly and goes over boundaries. I also thought about the fanaticism of the city of Jerusalem, thinking about my own fanaticism, located nowhere near religion. My Jerusalem was Liverpool, where The Beatles came from. I grew up wanting to visit Liverpool and my grandmother, who had a brother living in London and made many trips there, would tell me it was a terrible port city and I’ve not to this day visited it. The Beatles fascinated me after John Lennon’s assassination and I had all their albums. Then, once I had exhausted the albums, it was the bootlegs – I wanted to know everything. The enormous amounts of bootlegs available were primarily from the ‘Let It Be’ and ‘Abbey Road’ sessions and you can actually hear the studio chatter. I started to hear arguments and became more fascinated by these arguments. I went to record stores asking if they had any records of The Beatlesarguing, trying to pinpoint the moment when the collapse happened, as if I could find a moment as identifiable as the bullets that entered John Lennon’s body – that very place where the collapse occurred.

In 2003, for 30 minutes on the Internet, 150 hours of The Beatles last recording sessions, in crystal clear sound, were uploaded and I downloaded them, wondering for years afterwards what I was going to do with these recordings. For this project in Jerusalem I thought it would be interesting to use these tapes as a narration of the collapse of The Beatles as a way of talking about the collapse of Palestine and the Middle East. You had four Beatles and the four quarters of Jerusalem. So I went to this radio station in Ramallah, Radio Amwaj and they said this was a great idea because ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’, released in June 1967, was also released four days before the Six-Day War began. They asked me what I had in mind and I said maybe a three-hour programme and they said: ‘This is the Middle East, if your going to tell a story you have to go back to the beginning; its very genesis.’ They commissioned a ten-part radio series.

When I was producing the shows and listening to the 150 hours of material, there was one moment when Paul McCartney is creating the whole idea for the ‘Let It Be’ project, which was supposed to be called ‘Get Back’. The Beatles were supposed to return to the stage, which was something they hadn’t done since 1966, and McCartney was taking over the leadership role – John Lennon didn’t want it anymore and Brian Epstein had died of an overdose. There comes this balkanization of these different personalities making up this one group. Suddenly, it became one Paul, one John, one Ringo, one George. In some recordings, The Beatles were talking about going to places in the Middle East, to doing these concerts in places like Tripoli in Libya. There is this moment they’re joking about Paul’s beard and how they should do a concert in Jerusalem. Suddenly, something that was dealing with allegory and something seemingly disparate was actually a lot closer. These two dual timelines that happened during roughly the same period of time from the 1950s until the end of the 1960s and there were overlaps I thought were completely unlikely. It was a real discovery and it became like an archive project where one unearths or excavates something they hadn’t necessarily thought existed before but it was like it had been waiting there the whole time.

Michael Rakowitz, a conceptual artist based between Chicago and New York City, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Art Theory and Practice at the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University.

Reference

Rakowitz, Michael. “From Invisible Enemy to Enemy Kitchen Michael Rakowitz in Conversation with Anthony Downey.” Interview by Anthony Downey. Ibraaz. Ibraaz, 29 Mar. 2013.